Stefan Yong

1

The cultural history of the data centre in today’s Singapore begins with cyberpunk. But let’s be clear: it’s not that this marginal, paraliterary genre, pioneered by a handful of North American authors, succeeded in predicting the future — that is, our present. It’s instead that cyberpunk writing of the late 1980s and 1990s gave literary form to the uneven historical unfoldings of its own present, registering, with techno-Orientalist bewilderment, the contradictions between what was (even then) a novel application of state power and what were (not quite yet) the exigencies of a globalising, data-driven capitalism.

Neil Stephenson’s ‘Mother Earth Mother Board’ (1996) is one of the first great meditations on Internet infrastructures. It’s framed as a travelogue in which the author, a ‘hacker tourist’, documents and historicises the laying of a hybrid undersea-overland cable of then-unprecedented length, the Fiber-Optic Link Around the Globe (FLAG). Singapore appears as a hazy semipresence, which refuses to connect to this ambitious cable lay. Four years after Stephenson’s piece appeared in Wired magazine, the less evocatively named Southeast Asia-Middle East-Western Europe 3 cable, a project behind which Singapore threw its considerable island weight, would exceed FLAG in length by some 10,000 kilometres. SEA-ME-WE3 is still the world’s longest cable. Its administration lies with Singapore’s premier telecommunications company, Singtel, which the country’s government owns by way of its sovereign wealth fund Temasek Holdings.

To Stephenson’s name, we can add that of William Gibson and his notorious essay on Singapore, ‘Disneyland with the Death Penalty’. There, Gibson reflects upon the possible futures awaiting Singapore in the wake of the government’s sweeping turn to information technology. It’s 1993, and Singapore wants to bring itself online. Singtel’s manoeuvres in the international submarine cable industry are part of a wider set of state-directed shifts, collectively branded the ‘Intelligent Island’ initiative: computers in the home and the workplace; partial automation of air and maritime transportation infrastructure; recalibration of the workforce towards cognitive and service labour. For Gibson, Intelligent Island heralds an imminent collision. How will such a fastidiously administered society with its eminently functional infrastructures and its uncontested juridical punitivity, he asks, handle the pornographic weirdness, the anarchic ‘wilds’ of the same ‘X-rated cyberspace’ with which it now seems so desperate to interface?

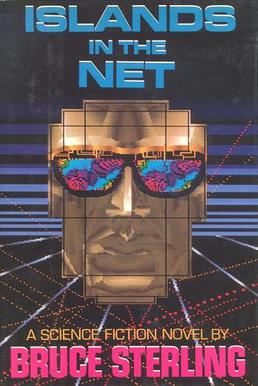

By the early 1990s, the economic hegemony of Japan was on the wane, and cyberpunk had yet to register the immense productive forces of a burgeoning Chinese capitalism. Singapore, then, served as a new or transitional repository for techno-Orientalist figurations. Consider a sequence from Bruce Sterling’s 1988 novel Islands in the Net, where the transcript of a parliamentary hearing on Singapore’s information governance interrupts the cyberpunk moment par excellence — plugging into the Net:

She sat, and turned the deck on, and loaded data. Pop-topped a jug of mineral water and poured it in a dragon-girdled teacup. She sipped, and studied her screen, and was absorbed.

The world around her faded. Into black glass, green lettering. The inner world of the Net.

PARLIAMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE

Select Committee on Information Policy

Public hearings, October 9, 2023

In Islands in the Net, cyberspace is not a representational abstraction, but a literary configuration of infrastructure space. On the novel’s first page, the protagonist trips on an electrical cable and falls hard on her face. Sterling describes the Net not as a matrix of information but as a world-historical integration of old-new communications infrastructure. Meanwhile, the eponymous ‘islands’ are ‘data havens’ that feed upon the global economy of information, ‘abstracting, condensing, indexing, and verifying’ the data that the Net economy requires for its operations. These ‘islands’ circumvent commercial protocols and privacy laws in order to store data indiscriminately and limitlessly. We could say, using twenty-first century terminology, that Sterling’s data havens blend the technical functions of the data centre with the murky juridical status of the special economic zone.

As an island haven of this sort, an ‘arrogant, and technologically reckless’ Singapore is home to ‘radical technical capitalists’, complete with their own space programme, who stand stubbornly opposed to the ‘globalists’, the ‘postindustrialists’, the ‘economic democrats’, the partisans of the harmonious global order promised by the Net. Suffice it to say that Sterling shares Gibson’s deep misgivings with the heavy hand of the country’s technocratic rule. The novel’s Singapore segment begins with airtight sociopolitical control, but spirals into chaos, and breathlessly concludes with riot, martial law, barricades in the streets, and a bloodbath in the Straits of Malacca. The encounter between Singaporean governance and global data flows must end in catastrophe. Otherwise, as Gibson frets, Singapore ‘will have proven it possible to flourish through the active repression of free expression. They will have proven that information does not necessarily want to be free’.

It’s an anxiety of the 1990s indeed, almost a quaint one to our ears; one cannot argue any longer, under conditions of today’s data-driven capitalism, that the Singapore government exercises a monopoly on the unfreedom of information. But the point was never to valorise cyberpunk for its predictive qualities. It was instead to reach for a more salutary insistence, namely that taking Singapore-oriented cyberpunk seriously will make it difficult to think Singapore’s encounter with global data technologies in isolation from cycles of accumulation and crisis at the level of the capitalist world-system. The data centre can and should be historicised — this principle is what we keep in mind as we close the novels and walk among the buildings.

2

Within Singapore’s short post-independence economic history, the origin of the government management of wired connectivity lies in the wired connectivity of government management. While Gibson and Sterling were publishing their cyberpunk opuses, the Singapore government was already several years deep into the first phase of its National Computerisation Plan: the Civil Service Computerisation Programme. The very first ‘data centre’ in Singapore would shortly appear, growing out of a move to centralise the National Computer Board’s (NCB) servers into three ‘hubs’ — one each for land, people, and enterprises. Singtel’s late 1990s purchase of National Computer Systems, the private-sector arm of the NCB, indicated a sharp convergence of government computerisation initiatives with government-linked expansion into regional and global telecommunications. More recently, the Smart Nation masterplan initiative, rolled out in 2014, promises to shape policy around the state’s accumulated hoards of population, environment, infrastructure, and surveillance data. ‘The government’, as the chief executive of the newly minted Government Technology Agency (GovTech) puts it bluntly, ‘has a lot of data’. When we examine Singapore’s data centres from the perspective of land zoning, electrical grid allocation, environmental policy, and the promotion of investment by multinational corporations, we also brush up against the place of data storage within the technological innovations of the state apparatus. State plans for Singapore’s data centres run in parallel track to the centrality of data to Singapore’s state planning.

The Singaporean data haven in Sterling’s novel had ‘the dignified cover of an address in Bencoolen Street, while the machinery hummed merrily in Nauru’. No such stark sundering of front-end commerce and back-end hardware is to be found in Singapore’s data centres. More often, the humming machinery is the dignified address. The practical desire for server co-location and proximity to cable landings sometimes appears indistinguishable from the wish-fulfillment of seamless connectivity. A technical specifications pamphlet for Global Switch’s data centre in Tai Seng outlines the structure’s cooling, connectivity, and security features, but also emphasises its location: 9 km from the Central Business District, 15 km from Changi Airport, a Mass Rapid Transit station within 10 minutes walking distance. Data centre clients, it would seem, want to feel linked not only to the cable networks of the wider Asia Pacific region from the Singaporean switch point, but also to the financial strongholds and transportation infrastructures of the island itself.

The production of urban space in Singapore, wherein space is subject to homogenisation, allotment, measurement, sorting, and categorisation, begs the question of the preconditions for such logistical ordering, or in other words the prior conditions of enclosure and dispossession that could have made such a formal spatial order operative in the first place. We know from historians like Loh Kah Seng that present patterns of residential and industrial zoning in Singapore could not have happened without large-scale evictions and resettlements of so-called ‘squatters’ in the wake of the devastating kampong fires of the 1950s and 1960s. Up to a third of Singapore’s data centres are located in what was once the Lorong Tai Seng kampong, where extant residents were all resettled into state-subsidised public housing in the three decades following a landmark August 1961 fire. A daring 1986 land swap by the Jurong Town Corporation, the government-linked agency behind Singapore’s post-independence industrialisation, would go on to cement the transformation of the old Lorong Tai Seng into the Tai Seng Industrial Estate, which now hosts local and regional data centre players like Starhub, ST Telemedia, Global Switch, Keppel DC REIT, and Equinix. Meanwhile, the social history of the Jurong Industrial Estate, home to many of Singapore’s remaining data centres, has yet to be written. State and state-friendly narratives of Singapore’s industrial explosion frequently emphasise the providential features of the invitingly vacant Jurong swampland, with its flat terrain and proximity to deep coastal waters, while glossing over the more stubbornly human subjectivities that had to be cleared out along with the trees. Land acquisition and squatter resettlement were the ineradicable undercurrents of the dizzying years of industrialisation. In the age of deindustrialisation and datafication, they remain critically unthought episodes in the data centre’s prehistory.

The zoning discourse of the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) defines data centre operations as ‘E-business activities regarded as industrial uses’. Once designated as industrial buildings, Singapore’s data centres must be constructed according to state guidelines on fairly rigid ‘use quantums’, such that a minimum of 60% of the building’s gross floor area (GFA) must be used for ‘industrial purposes’ — in this case, server racks. Just as containerisation in shipping forced a degree of abstraction by shifting the standard unit of measurement for commodities from weight to volume, so too do state agencies like the URA domesticate data centre functions by incorporating them into established spatial frames of calculation and measurement. Zoning and urban planning are the spatial techniques that attempt to render data centres knowable to the state. This is state logistics understood as ‘a particular, abstract representation of space’ (Toscano), a ‘volumetric urbanism’ (McNeill) of which Singapore is an avant-garde practitioner.

3

The Centre for Strategic Futures (CSF) is a think tank of the Singapore government, housed within the executive agency known as the Prime Minister’s Office. In his foreword to the 2019 issue of the CSF’s publication Foresight, Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong describes the project of futures planning as an interminable ‘work that will never be done’, as an intellectual project anchored in ‘developing contingency plans free from the day-to-day demands of operational responsibilities’. This is not speculative fiction, but speculative governance. The nation-state must prioritise flexibility and resilience, and must account and design for what Lee calls ‘black swan events’ and inevitable system failures; the nation-state must be run, in short, like a data centre.

If, as the CSF’s Senior Advisor goes on to write, ‘it is in our DNA as a country’ to respond to ‘complexity, uncertainty, and accelerating change’, then the state governance of data centres finds a shining prefigurative authorisation in Singapore’s colonial past, so that the colonial vision of entrepot trade and the contemporary vision of data circulation partake in the same genius of foresight: ‘Just as Raffles made Singapore a free port in 1819, welcoming traders from any country, Singapore today could be a free data port’.

Does accelerating data centre construction on the island call back to imperial trade strategy in the same manner that fibre-optic cables retrace the undersea pathways of colonial telegraph lines? In either case, it’s plain that this historical repetition is neither natural nor guaranteed. The state intelligentsia knows that physical geography alone cannot, or cannot any longer, secure Singapore’s position as a hub in a network. Like the move to reassert Singapore’s transshipment dominance with the decades-long Tuas Mega Port project, the government’s support for the data centre industry expresses a commitment to built form. It is these plans for construction, and not happy accidents of latitude, that will allow Singapore to continue understanding itself as a polestar orienting oceanic and digital channels of circulation. Therecapitulation of logics of colonial economy is not an evolutionary spasm, but a state-directed project.

A 2017 renaming of the new data centre hub in the Jurong Industrial Estate, from the bland ‘Singapore Data Centre Park’ to ‘Tanjong Kling’, raises even more baleful colonial spectres. Ostensibly, the change associates data centre land nominally with existing industrial land also called Tanjong Kling. Urban planners seem to have forgotten the history of this word kling,or keling, and its use in the colonial periodas a racial slur. A once neutral Malay-language designation for the South Asian Kalinga kingdom had, by the early twentieth century, become a derogatory term for any person of South Asian descent, after kling was also generally understood to reference the jangling restraints of South Asian indentured labourers set to work in chain gangs throughout British Malaya. Indeed, what is now Chulia Street in Singapore’s downtown core was ‘Kling Street’ until the 1920s, when the Indian Association of Singapore objected to the name and successfully lobbied for a change.

Today, one can walk around the Tanjong Kling park and see not towering data centres but empty allotments and glacial construction activities. Here and elsewhere, labourers from the Indian subcontinent constitute a visible majority among Singapore’s construction workers. Their working conditions are framed by a backdrop of debt-financed migration, and are sited at the conjunction of poverty wages, weak labour laws, and rampant intimidation tactics on the part of construction bosses. To set South Asian labourers to work building data centres in Tanjong Kling is to then mark their workplaces with the stamp of an earlier (but perhaps not, after all, so different) regime of labour migration and uneven development. In ‘Mother Earth Mother Board’, Stephenson offers the following adage: ‘Everything that has occurred in Silicon Valley in the last couple of decades also occurred in the 1850s’. This axiom remains instructive as a polemical corrective rather than an analytical truth. Its suspicion of analytical presentism is welcome, but it does not mean that the answer to the mysteries of the data centre is to be found in the innermost logics of ‘copper cable colonialism’ (Starosielski). In that spirit, it would also be mistaken to claim that everything that has occurred in the Singaporean governance of data centres has already occurred in cyberpunk. The final call, towards which this essay is an assemblage of preliminary attempts, will instead be to multiply the genealogies of the data centre, in service of an attentiveness to the equally multiple political possibilities adequate to an era for which the data centre is the unassuming symbol.