Maya Indira Ganesh and Johannes Bruder

At the end of a two hour-long tour through the bowels of their brand new ‘server hotel’ near Basel, Switzerland, the CEO brought us back to the meeting room and signaled that he would now take questions. Our colleague raised his hand and asked, jokingly, if they were afraid that some of us would break in at night, now that we know everything about the myriad security mechanisms that the company had installed. ‘We’re actually not afraid that someone would break into the physical building,’ the CEO replied, ‘the problem is that we are promiscuously connected’.

‘Promiscuous connectivity’ sits at the heart of the planetary-scale infrastructure that so many data centres now form part of: the cloud. Whether the servers in a data centre carry highly sensitive data of financial transactions or publicly accessible collections of holiday photos, they depend on promiscuous connectivity to guarantee continual and remote accessibility. A bit like a multinational corporation, the cloud ‘offers a vision of globalization’ – ‘a coalition of geographic areas that move capital and resources through the most efficient path’ (Hu). The cloud seemingly hovers in between or above its physical infrastructure – a pledge of ubiquity and infinity. As a global political operation, it emphasizes redundancy and infrastructural detachment, or the general expendability of its infrastructural elements.

In a piece titled ‘Could we blow up the internet’, Tim Maughan comes to the conclusion that a cyber attack is much more effective in terms of potential collateral and cost than any imaginable attack on the physical infrastructure of the cloud. If we believe the CEO of the aforementioned server hotel, this threat applies to any kind of data centre that provides remote access to data and computing capacities. However, a quick search reveals that cloud infrastructure facilities are typically replete with perimeter fences, security guards, surveillance technologies, biometric readers and reinforced steel cages, designed to keep out any unauthorized personnel. In a video presentation about Google’s data centres, a top executive describes the various levels of physical security that someone trying to get into the centre would have to pass through. The rooms housing the actual server racks are akin to a sanctum sanctorum. Only those with the highest security clearance proceed all the way through.

Despite the fact that promiscuous connectivity is the most disquieting liability of data centres, their physical fortification proceeds unabatedly. As the only visible element of a system that ‘buries or hides its physical location by design’ (Maughan), the data centre as ‘thing’ provides singular opportunities to market the resilience of the system as a whole.

It is this moment of Gestalt thinking, when figure and ground simultaneously merge and separate, that it becomes difficult to know what exactly we are encountering – the whole, or something slightly more than the sum of its parts? How do we study and make sense of the apparent contradiction in that the data centre is an expendable infrastructural element, but that its significance ties to the infrastructural promise it exemplifies, a promise of resilience that applies to the system as a whole?

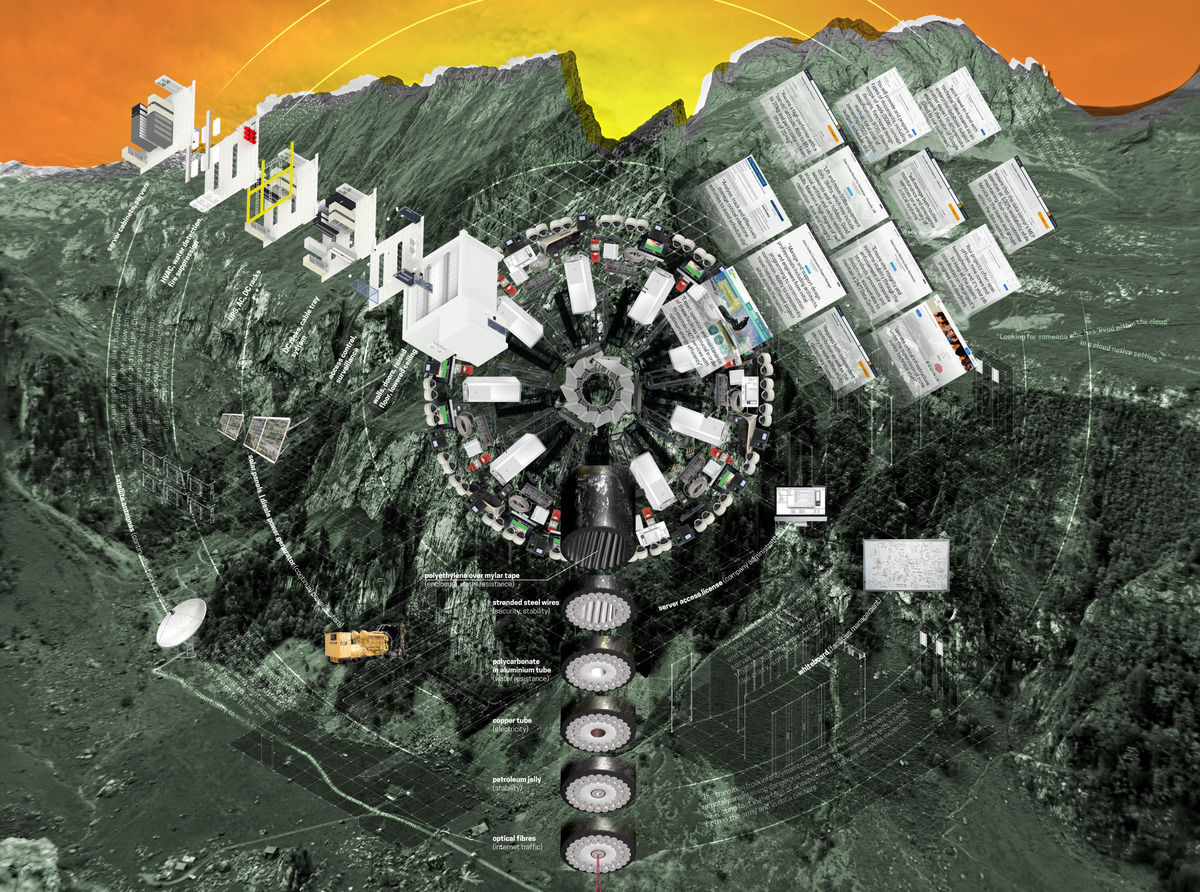

In this text, we assess the relationship between data centres and the cloud through the methodological device of the cosmogram: ‘a text that results in a concrete practice and set of objects, which weave together a complete inventory or map of the world’ (Tresch). Writing, art, and investigations tell of pre-histories of data farms and cloud infrastructures through the lives of older media (Hu, Peters); by identifying their material components (Burrington, Starosielski); their ability to reshape notions of sovereignty (Amoore, Bridle); and through new figurations of knowledge in terms of spatiality (Bratton). In these accounts, the boundaries between the encompassing system – the cloud – and its constituting elements – i.e., the data centre – tend to blur in favor of systemic logics. Cosmograms present a vision of the relation between part and whole. They draw inspiration from ancient temple architecture, which strives to represent the cosmos by laying out and reinforcing the relations between humans and other beings. As such, they register how science and technology bring into the world not only facts and artefacts but also narratives, structures and feelings. Cosmograms are as much performative and reflexive as they are representative and classifactory. In other words, they intervene in the world and provoke questions about their own status, limits and qualifications.

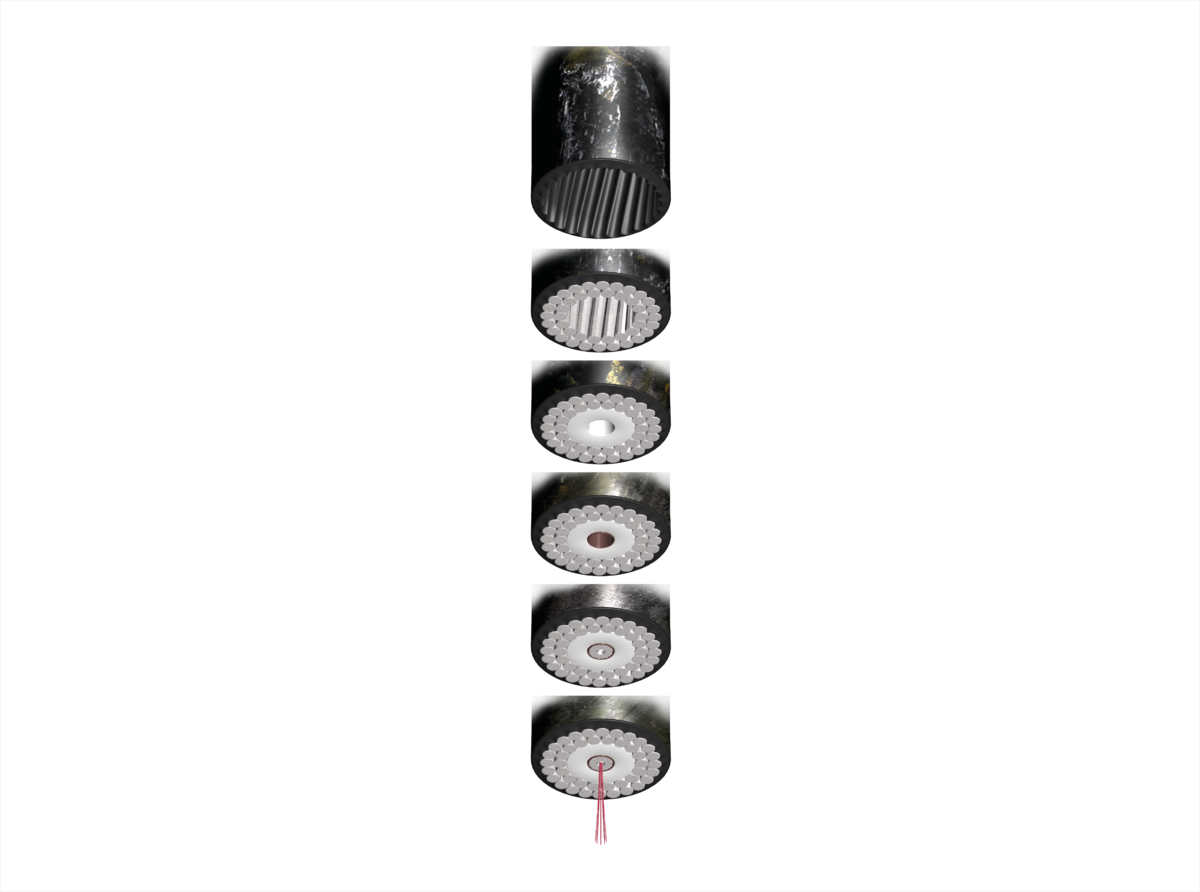

In thinking with and through cosmograms, we want to suggest a fork emerging from the study of the cloud in terms of the material components that operationalize it – undersea cables, servers, security, storage and so on. If this material assembly shows us how things are actually materially architected (and thus supports the infrastructural promise of the cloud), ‘cosmogram thinking’ allows us to appreciate the uncertain ‘cultural choreographies’ at play, the ‘contestations, additions, deletions and replacements’ (Tresch) that disturb the holism proposed by our internal maps of how the cosmos is architected.

The primary infrastructural promise of the data centre is that it will provide jobs to wherever data centres come to be housed. When Facebook opened its third data centre in Luleå, Sweden, its mayor was happy that the land and affordability of energy could allow the data centre to ‘grow’. But he was most enthusiastic about the jobs that would come to the region, even if he was not very sure what they would be or what people would do.

Unfortunately, this rather classic infrastructural promise rarely materializes. Large-scale data centre facilities tend to remain’ in-between spaces’ (Johnson), built in accordance with the principles of global logistics, yet managed as an agglomeration of machines, including the now infamous human-exclusion zones. When viewed through the daily work of a data centre manager or technician – persons with little executive power, but with security clearance to inhabit the inner chambers of a data centre – an alternative microcosm of the cloud takes shape.

Advertisements for data centre jobs tend to emphasize the need not only for management skills and technical know-how but also physical endurance. An Amazon data centre technician role ‘has a physical component requiring the ability to lift & rack equipment up to 40lbs; it may require working in cramped spaces or elevated locations, dominated by an incessant, noisy hum that tend to ridicule the adhering to health & safety guidelines. On a Quora thread about working at a data centre, ‘George Henry’ asks: ‘Can you work in an environment where you have spoken to not one other person for 8 hours?’ And he notes that while it is not as good as working ‘at corporate’, still, ‘you are lucky to get a desk. As the team grows, your work environment improves (12 or so people usually warrants free food and video game consoles)’.

Salute Inc, an organisation founded by a former US Army reservist, Lee Kirby, tries to employ veterans in data centre management. The most significant skill might be endurance: ‘Kirby argues that the transition from infantryman to data center technician is easy: working remotely, maintaining dangerous equipment, communicating with a team and acting fast in the face of unexpected situations are skills expected both in the army and in data centers’.

Cloud Cosmogram. To view the image in full size, visit this link. Or download the pdf.

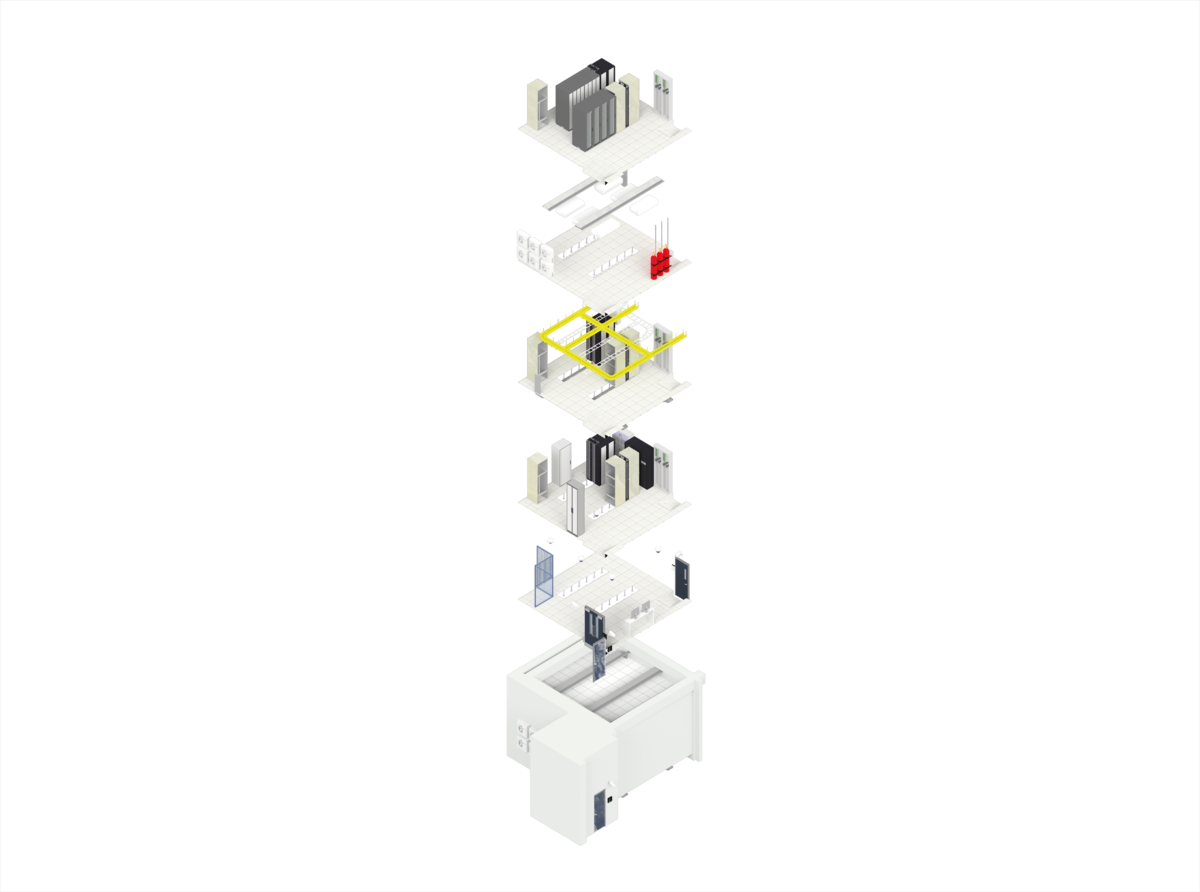

Taking a step back from seeing the cloud as a medium that virtualizes social relations, we take the technicalities, standards and certificates that guide data centre operations to compose an alternative cosmogram of the cloud. In so doing, we move away from the metaphorical elusiveness implied by the figure of the cloud to ask how data centre operations enable, challenge, and to some degree replace, traditional sociality through the organizational intricacies of ‘post-human institutions’: a ‘new form of architecture for data and machines … almost liberated from human intervention and entirely shaped by technological rationales’. Our cosmogram does not reveal a disguised materiality – it is neither another mapping of its very material infrastructure nor a visualization of its equally material carbon footprint. Instead, we concentrate on the co-location of objects and technical practices that determines the place of the human in the data centre. ‘To understand how people inhabit this world… we must shift our attention from the congealed substances of the world, and the solid surfaces they present, to the media in which they take shape and in which they may also be dissolved’ (Ingold).

Approached from this perspective, the cloud appears fragile, physical, precious; neurotic even, in that it is constantly in need of maintenance and care; always insecure, despite its physical fortification through tailor-made architectures. Orchestrated through data centre operations, the cloud is constantly evolving computational and logistical challenges that human operators must take on in highly personal and material ways. The data centre is a new kind of architectural interface, the ‘post-human institution’ that organises human/non-human cohabitation as the labour of relentless trouble-shooting.

John Tresch writes about a specific cosmogram, the tabernacle, that ‘… the day they stop doing all the different kinds of work that built the temple, when the people enter it, when the priests have accomplished all the necessary rites in the proper order, God comes to the Hebrews: in the form of a cloud, he fills the tent’. Ultimately, however, the tabernacle is a design for a nomadic institution. ‘What is fundamental’, Tresch writes, ‘is that the link with God is made possible by the mediation of a construction described in an extremely detailed and technical manner and this construction has a place for all of society and all of nature’.

The technicalities, standards and certificates that guide the labour of data centre managers and engineers provide an alternative cosmogram, embodying the relations between humans, nature and logistical machines. Architects are now rushing to design data centres as aestheticized machine landscapes or avant-garde leisure zones (see, for example, OMA’s Museum in the Countryside), to appeal to those whose ‘chronopolitics’ (Sharma) are entangled with the promise of remote and relentless accessibility. If Tresch’s invocation of the temple seems a stretch, consider Liam Young’s description of data centres as ‘typologies without history’. ‘Should we visit them like churches?’, he asks in an interview with Strelka Mag. ‘Or should we wander through them like we wander through a forest? Maybe we go on picnics to the data centre like we once did to rolling hills. Maybe they become occupiable territories in ways that they’re not allowed to be right now’.

The sacred geometries of the data centre materialize a certain ‘infrastructural reason’ (Carse), where human labour is defined through the operational politics of the cloud and an intimate relationship with the machine. In these spaces, the human must be adept at problem solving by trial and error, but is, at other times entirely alone with the cloud, or machine-like herself. As Tim Burke writes, my ‘favorite data center was a building so hardened it was an accidental Faraday cage. When I went in, I knew that communication with the outside world was going to be severed like a cut ethernet cord. The data center was where I went to get away. It was where I went to think’.

Since the construction of early mainframe computers, shared computing facilities have provided models of how humans and computers might beneficially interact. Yet, in contrast to the emphasis on spatial co-habitation that high-flying architectural visions provide, we think of historical time-sharing systems as well as contemporary data centres as experiments in attuning the labour of humans to the rhythms of the machine. After all, a data centre ‘is not a building full of computers but rather a computer with architectural qualities’ (LeCavalier). The disorienting figure-ground relationship between the cloud and its data centres and other things that are part of our internet cosmology, disrupts and confuses our notion of what those alleged ‘post-human institutions’ ultimately involve: more, and constant, human dedication to and intimacy with the machine. ‘There is no room for a segregation mind-set’, John Oyhagaray emphasises. ‘In the data center, everyone is responsible for system uptime’.